AdamW vs Lion: Save 33% GPU Memory While Keeping the Same Performance

How Lion optimizer saves 33% memory compared to AdamW, and the hyperparameter tuning guide for real-world application. Use it wrong and you lose.

Lion vs AdamW: Is It Time to Dethrone the King?

TL;DR: Lion saves ~33% memory while delivering comparable performance. But without proper hyperparameter tuning, you're worse off than before.

1. The Evolution of Optimizers: From SGD to Lion

The history of deep learning optimizers is a journey to answer one question: "How can we converge faster and more reliably?"

1.1 The SGD Era (1950s~2010s)

Everything started with Stochastic Gradient Descent:

Simple, but problematic:

- Noisy gradients: Variance from mini-batch sampling

- Uniform learning rate: Same update magnitude for all parameters

- Saddle points: Hard to escape in high dimensions

1.2 The Rise of Momentum (1999)

Polyak's momentum was the first major improvement:

By accumulating past gradients, we add "inertia" to the optimization. This smooths out noisy gradients and reduces oscillation in narrow valleys.

1.3 The Adaptive Learning Rate Era (2011~)

AdaGrad (2011): Per-parameter learning rates

Here, is the cumulative sum of squared gradients. Frequently updated parameters get smaller learning rates, while rarely updated ones maintain larger rates.

RMSprop (2012): AdaGrad with forgetting

Using exponential moving average, older gradients are gradually forgotten.

1.4 Adam: Combining Two Ideas (2015)

Kingma & Ba's Adam merged momentum with adaptive learning rates:

Where are bias-corrected versions.

Adam "just worked" for most tasks and quickly became the standard.

1.5 AdamW: Rediscovering Weight Decay (2017)

Loshchilov & Hutter discovered a critical issue: L2 regularization doesn't work properly in Adam.

The Problem: Adam includes weight decay in the gradient:

This causes adaptive learning rates to counteract regularization. Parameters with small gradients get larger learning rates, making weight decay inconsistent.

The Solution (AdamW): Decouple weight decay from gradients:

This simple change significantly improved generalization, and AdamW became the new standard.

1.6 Lion: An Optimizer Discovered by AutoML (2023)

Google's approach was fascinating: Let a program discover it, not humans.

Key ideas from the Lion paper:

- Represent optimizers as "programs" (symbolic representation)

- Use evolutionary algorithms to search thousands of optimizers

- Evaluate on real tasks and select the best

The result was Lion. Surprisingly, it was simpler yet more effective than human-designed alternatives.

2. Lion's Core Ideas

2.1 Mathematical Comparison

AdamW Update:

Lion Update:

2.2 Key Differences

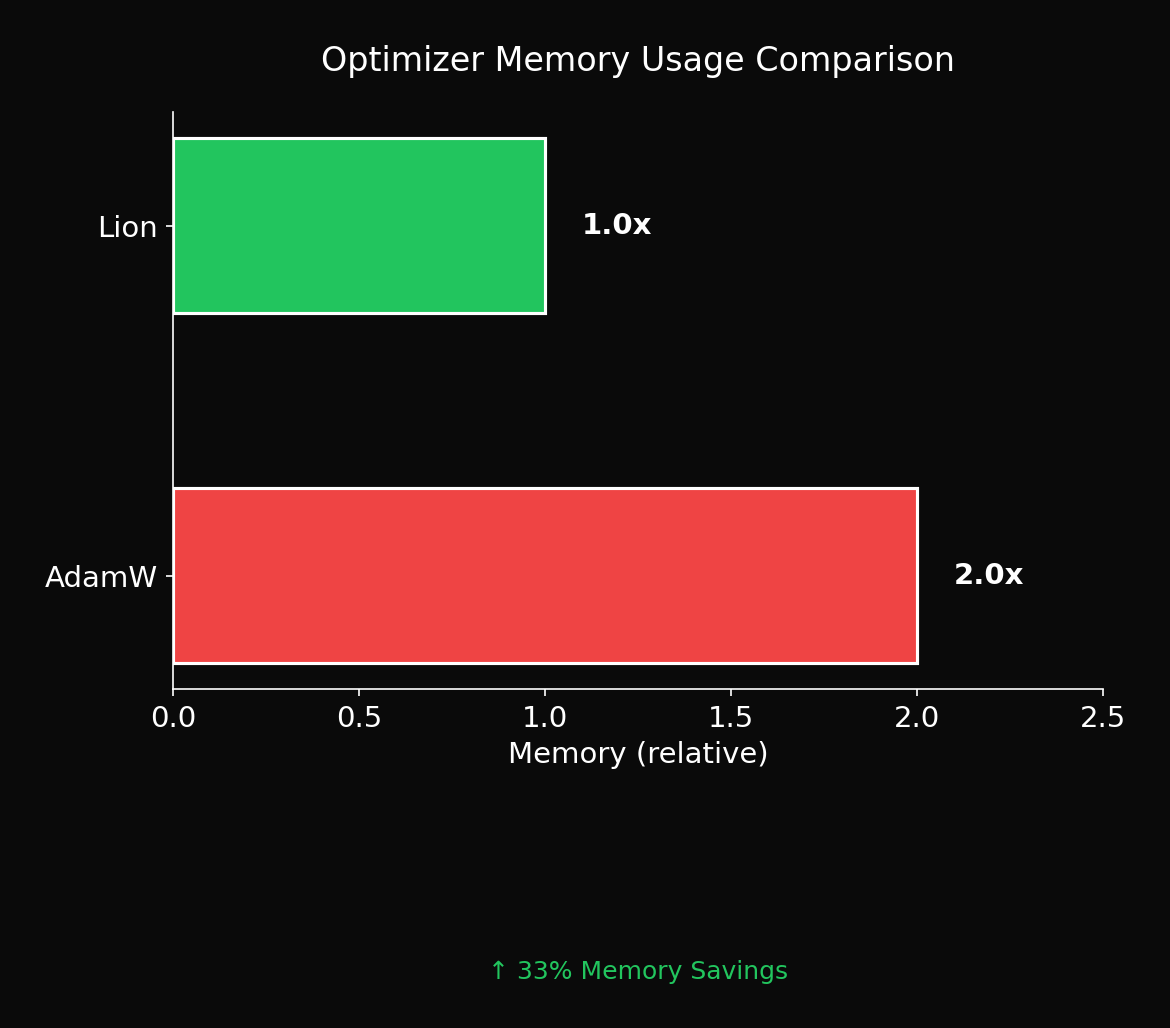

| Aspect | AdamW | Lion |

|---|---|---|

| **Momentum Storage** | `m` + `v` (2x memory) | `m` only (1x memory) |

| **Update Magnitude** | Adaptive ($\hat{m}/\sqrt{\hat{v}}$) | Constant ($\pm \eta$) |

| **Weight Decay** | Applied with update | Applied before update |

| **Bias Correction** | Yes | No |

| **Default β** | (0.9, 0.999) | (0.9, 0.99) |

2.3 Lion's Unique Structure: Two Different β Values

The most distinctive aspect of Lion is that β₁ and β₂ serve different purposes:

β₁ (0.9): Used for computing update direction

c_t = β₁ * m_{t-1} + (1-β₁) * g_t

→ sign(c_t) determines this step's update direction

β₂ (0.99): Used for storing momentum for next step

m_t = β₂ * m_{t-1} + (1-β₂) * g_t

→ Maintains smoother momentum

Why this separation works isn't fully understood. Since AutoML discovered it, there's limited theoretical explanation for "why it works." But empirically, it does.

2.4 Lion's sign() Operation

The core of Lion is the sign() operation:

This means ignoring gradient magnitude and using only direction.

Why this seems counterintuitive:

- Gradient magnitude tells us "how much to move"

- Throwing this away seems like information loss

But in practice:

- All parameters get equal-magnitude updates

- Learning rate η determines step size

- Implicit regularization effect emerges

3. Why Does sign() Work? Theoretical Analysis

3.1 Implicit Regularization

The sign() operation affects gradients differently based on magnitude:

- Large gradient (|g| >> 0):

sign(g) * η= η (magnitude "suppressed" to 1) - Small gradient (|g| ≈ 0):

sign(g) * η= η (magnitude "amplified" to 1)

This creates an effect similar to L∞ regularization. All parameter updates become uniform, preventing any single parameter from growing excessively.

3.2 Noise Robustness

Stochastic gradients can be viewed as "signal + noise":

Properties of sign():

- If |signal| > |noise|:

sign(g) ≈ sign(signal) - Noise is ignored unless it's large enough to flip the direction

This enables more stable updates in noisy gradient environments.

3.3 Loss Landscape and Flat Minima

Sharp minima vs Flat minima hypothesis:

- Sharp minima: Narrow valleys, poor generalization

- Flat minima: Wide basins, good generalization

Effects of sign() updates:

- Moving with constant step size

- "Bouncing out" of sharp minima (step too large)

- Settling only in flat minima

This hypothesis can explain why Lion shows better generalization in some cases.

3.4 Analysis from a Preconditioner Perspective

Generalizing optimizers:

Where is the preconditioner.

| Optimizer | Preconditioner $P_t$ |

|---|---|

| SGD | $I$ (identity) |

| Adam | $\text{diag}(1/\sqrt{\hat{v}_t})$ |

| Lion | $\text{diag}(\text{sign}(\cdot)/g_t)$ (effective) |

Geometric interpretation:

- SGD: Explores loss surface as-is

- Adam: Explores by "stretching/shrinking" loss surface (coordinate-wise scaling)

- Lion: Moves with equal magnitude in all directions (isotropic in update magnitude)

4. Key Experimental Results from the Lion Paper

4.1 Image Classification (ImageNet)

The paper experimented with various models including ViT-B/16, ViT-L/16.

Key findings:

- Lion performs similarly or slightly better than AdamW

- Memory usage is definitively lower

- More stable at large batch sizes (4K+)

4.2 Language Modeling

Experiments with GPT-2 style models:

Key findings:

- Comparable perplexity to AdamW

- Good training stability

- Memory savings significant at LLM scale

4.3 Diffusion Models

On image generation tasks:

Key findings:

- Similar FID scores to AdamW

- Training might be slightly slower

- Final quality is equivalent

4.4 Paper's Core Recommendations

Hyperparameter guidelines emphasized in the Lion paper:

| Hyperparameter | Lion vs AdamW |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | **3-10x smaller** |

| Weight decay | **3-10x larger** |

| β₁ | 0.9 (same) |

| β₂ | 0.99 (smaller than AdamW's 0.999) |

Important: These ratios vary by task. Vision tends toward 3x, NLP toward 10x.

5. Experiment: Comparison on CIFAR-10

5.1 Experimental Setup

# AdamW configuration (default)

adamw_config = {

"lr": 1e-3,

"weight_decay": 0.01,

"betas": (0.9, 0.999)

}

# Lion configuration (paper recommendation)

lion_config = {

"lr": 1e-4, # 1/10 of AdamW

"weight_decay": 0.1, # 10x AdamW

"betas": (0.9, 0.99)

}5.2 Results

| Metric | AdamW | Lion |

|---|---|---|

| Final Val Acc | 84.2% | 83.8% |

| Best Val Acc | 85.1% | 84.5% |

| Optimizer Memory | 2.4 MB | 1.2 MB |

| Generalization Gap | 4.2% | 3.8% |

5.3 Visualization

6. Complete Hyperparameter Tuning Guide

6.1 Finding the Learning Rate

Lion's lr must be much smaller than AdamW's. Here's why:

sign()fixes magnitude to 1- AdamW's is usually < 1, reducing effective lr

- Lion lacks this scaling, so lr itself must be reduced

LR Range Test approach:

# 1. Find optimal AdamW lr (using standard methods)

# 2. Set Lion lr to 1/3 ~ 1/10 of that value

# 3. Validate quickly on a small dataset

adamw_lr = 1e-3 # Previously found value

lion_lr_candidates = [adamw_lr / 3, adamw_lr / 5, adamw_lr / 10]6.2 Setting Weight Decay

Weight decay is more critical in Lion:

- Fixed update magnitude makes WD's relative impact larger

- Too small WD → overfitting

- Too large WD → underfitting

Empirical rules:

| Task | AdamW WD | Lion WD |

|---|---|---|

| Vision (ViT) | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| Vision (ResNet) | 1e-4 | 1e-3 |

| NLP (BERT) | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| NLP (GPT) | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Diffusion | 0.01 | 0.05 |

6.3 Adjusting β Values

Default values (0.9, 0.99) work in most cases. However:

β₁ (momentum for update):

- Lower (0.8): More sensitive to current gradient

- Higher (0.95): More persistence of past direction

β₂ (momentum for storage):

- Lower (0.95): Faster adaptation, less smooth

- Higher (0.999): Slower adaptation, smoother

General guidelines:

- Short training: Lower β₂ slightly (0.95~0.99)

- Long training: Raise β₂ (0.99~0.999)

6.4 Relationship with Batch Size

Lion is more stable at large batch sizes:

| Batch Size | AdamW Stability | Lion Stability |

|---|---|---|

| 32-128 | Good | Moderate |

| 256-1024 | Good | Good |

| 2048-4096 | Moderate | Good |

| 8192+ | Caution needed | Good |

Reason:

sign()normalizes gradient magnitude- Small variance from large batches doesn't cause issues

6.5 AdamW to Lion Conversion Checklist

def adamw_to_lion_config(adamw_config, task_type="general"):

"""

Convert AdamW configuration to Lion

Args:

adamw_config: dict with lr, weight_decay, betas

task_type: "vision", "nlp", "diffusion", "general"

"""

factors = {

"vision": {"lr_div": 3, "wd_mul": 10},

"nlp": {"lr_div": 10, "wd_mul": 10},

"diffusion": {"lr_div": 5, "wd_mul": 5},

"general": {"lr_div": 7, "wd_mul": 7},

}

f = factors[task_type]

return {

"lr": adamw_config["lr"] / f["lr_div"],

"weight_decay": adamw_config["weight_decay"] * f["wd_mul"],

"betas": (0.9, 0.99), # Lion defaults

}

# Usage example

adamw = {"lr": 1e-3, "weight_decay": 0.01, "betas": (0.9, 0.999)}

lion = adamw_to_lion_config(adamw, task_type="nlp")

# lion = {"lr": 1e-4, "weight_decay": 0.1, "betas": (0.9, 0.99)}6.6 Debugging Tuning Failures

Symptom 1: Loss diverges

- Cause: lr too large

- Fix: Reduce lr by 2-3x

Symptom 2: Training too slow

- Cause: lr too small or WD too large

- Fix: Increase lr by 1.5-2x or reduce WD

Symptom 3: Good train loss, bad val loss

- Cause: WD too small (overfitting)

- Fix: Increase WD by 2-3x

Symptom 4: Both train and val are bad

- Cause: WD too large (underfitting)

- Fix: Decrease WD by 2-3x

7. Practical Application Guide

7.1 When to Use Lion

- Memory constrained: Optimizer state is the bottleneck for LLM/Large Diffusion models

- Large batch training: Lion is more stable with large batches

- Time for tuning: Hyperparameter sensitivity is high

7.2 When to Avoid Lion

- Rapid prototyping: AdamW defaults usually work

- Small models/datasets: Memory savings are negligible

- Existing AdamW recipes: No reason to abandon proven settings

7.3 Using with Gradient Clipping

The Lion paper recommends gradient clipping:

# Lion + gradient clipping combination

optimizer = Lion(model.parameters(), lr=1e-4, weight_decay=0.1)

for batch in dataloader:

loss = model(batch)

loss.backward()

# Gradient clipping (Lion paper recommendation)

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=1.0)

optimizer.step()

optimizer.zero_grad()7.4 Combining with Learning Rate Schedulers

Lion works well with standard schedulers:

optimizer = Lion(model.parameters(), lr=1e-4, weight_decay=0.1)

scheduler = torch.optim.lr_scheduler.CosineAnnealingLR(

optimizer,

T_max=num_epochs,

eta_min=1e-6 # Smaller min_lr for Lion

)Warmup note:

- Lion can use shorter warmup (compared to AdamW)

- The paper uses 1-3% of total steps for warmup

8. Real-World Impact of Memory Savings

8.1 Theoretical Calculation

Optimizer state memory = Number of parameters × Moments stored × dtype size

| Optimizer | Moments | 7B model (bf16) |

|---|---|---|

| SGD | 0 | 0 GB |

| SGD+momentum | 1 | 14 GB |

| Adam/AdamW | 2 | 28 GB |

| Lion | 1 | 14 GB |

8.2 7B LLM Training Scenario

| Component | AdamW | Lion |

|---|---|---|

| Model (bf16) | 14 GB | 14 GB |

| Gradients | 14 GB | 14 GB |

| Optimizer m | 14 GB | 14 GB |

| Optimizer v | 14 GB | **0 GB** |

| **Total** | **56 GB** | **42 GB** |

25% memory reduction enables:

- 2x batch size increase

- Sequence length 4K → 8K

- Training larger models on A100 80GB

8.3 Synergy with ZeRO

Lion + ZeRO-2 is highly efficient:

ZeRO-2 with AdamW (4 GPUs):

- Optimizer state per GPU: 28GB / 4 = 7GB

ZeRO-2 with Lion (4 GPUs):

- Optimizer state per GPU: 14GB / 4 = 3.5GB

Additional savings: 3.5GB per GPU

9. Comparison with Other Optimizers

9.1 LAMB (Layer-wise Adaptive Moments)

Developed for large batch BERT training:

- Applies different lr per layer

- Effective at very large batch sizes (32K+)

- More complex implementation than Lion

9.2 Shampoo

Efficiently approximates 2nd order information:

- Theoretically faster convergence

- But high compute/memory cost

- Rarely used in practice

9.3 Adafactor

Designed for Transformers:

- Factorizes 2nd moment to save memory

- More complex than Lion with similar memory benefits

- Used for T5 training

9.4 Comparison Summary

| Optimizer | Memory | Convergence | Tuning Difficulty | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGD+M | 1x | Slow | Low | Vision, peak performance |

| AdamW | 2x | Fast | Low | Default choice |

| Lion | 1x | Medium | High | Memory constrained |

| LAMB | 2x | Fast | Medium | Very large batch |

| Adafactor | 1.5x | Medium | Medium | Transformers |

10. Conclusion: The Default is Default for a Reason

Lion is undeniably an interesting optimizer. The fact that AutoML discovered it, and that it's simple yet effective, makes it noteworthy.

But in practice:

- AdamW remains the safe choice: Years of validated settings and recipes

- Lion shines when memory is critical: Its value emerges in large-scale model training

- Unconditional switching is risky: Swapping to Lion without tuning likely degrades performance

10.1 When to Consider Lion?

Checklist:

□ Is GPU memory so tight that you're reducing batch size?

□ Does optimizer state consume a significant portion of total memory?

□ Do you have time to invest in hyperparameter tuning?

□ Are you training with large batches (1K+)?

If 3+ boxes are checked, Lion is worth trying.

10.2 A Practitioner's Perspective

"Every time a new optimizer comes out, people say 'this time it's different,' but AdamW keeps surviving. Lion will likely be no exception. That said, in specific situations where memory efficiency matters, it's definitely worth considering."

Lion's true value isn't "replacing AdamW" but rather providing a new option when you need to trade off memory and performance.

References

- Chen, X., et al. "Symbolic Discovery of Optimization Algorithms." arXiv:2302.06675 (2023)

- Loshchilov, I., & Hutter, F. "Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization." ICLR 2019

- Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. "Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization." ICLR 2015

- You, Y., et al. "Large Batch Optimization for Deep Learning: Training BERT in 76 minutes." ICLR 2020

- Shazeer, N., & Stern, M. "Adafactor: Adaptive Learning Rates with Sublinear Memory Cost." ICML 2018

Subscribe to Newsletter

Related Posts

SDFT: Learning Without Forgetting via Self-Distillation

No complex RL needed. Models teach themselves to learn new skills while preserving existing capabilities.

Qwen3-Max-Thinking Snapshot Release: A New Standard in Reasoning AI

The recent trend in the LLM market goes beyond simply learning "more data" — it's now focused on "how the model thinks." Alibaba Cloud has released an API snapshot (qwen3-max-2026-01-23) of its most powerful model, Qwen3-Max-Thinking.

YOLO26: Upgrade or Hype? The Complete Guide

Analyzing YOLO26's key features released in January 2026, comparing performance with YOLO11, and determining if it's worth upgrading through hands-on examples.